"Inspiration is for amateurs - the rest of us just show up and get to work." - Chuck Close

Hardware requires a level of precision, things like symmetry and dimensional tolerances, that jewelry does not. One of the key elements that facilitates the design and development of our cabinetry hardware is 3D computer modeling. It enables us to work more seamlessly such that we can tweak the shapes, print them out, and hold them in our hands all in the same day. The starting point for Peak was in the forms we had developed for jewelry. Because this was our first jewelry collection modeled in in Rhino, a 3D modeling software, the process began by scaling the parts up in size. Our Form2 3D printer has become one of our most valuable tools because it facilitates the speed of iterations by allowing us to quickly produce prototypes in order to refine the details of a design. This is of particular importance for hardware because we need to know how the piece feels in your hand. How the fingers wrap around the handle, how they feel between the stand-offs, and the weight and form within the palm, for example. All these functional elements are as carefully considered as the visual aesthetic.

In addition to “in house” tools, we rely heavily on our network of skilled craftsmen and craftswomen to navigate this part of the process. We greatly value the mastery of their trade and all they bring to the table as well their willingness to share it! We have worked diligently to build these relationships, and feel strongly about supporting what has become a dying breed of American manufacturing that caters to small, independent designers. These are people who care about their craft, and are vested in the outcome. They are also willing to take on both modest as well as large orders without a second thought.

All of our hardware is cast and our caster plays a critical role in assessing the viability of designs for the casting process. He will often weigh in on potential issues early on in order to help us achieve a successful workflow in production. In the initial stages of developing the designs for our Peak collection, he voiced concerns about the thickness of some of the pieces. Casting thick parts can be difficult because thicker parts take longer to cool, and the longer it takes to cool the more likely you are to get surface imperfections or what is called “porosity.” At his suggestion, we hollowed out the backs of the thicker pieces to address this. However, when we printed prototypes of these components and held them in our hands, it was clear that this was not an appealing solution since it looked substantial from the front but felt hollow in the back. This is a perfect example how we are always balancing technical challenges with those of aesthetics.

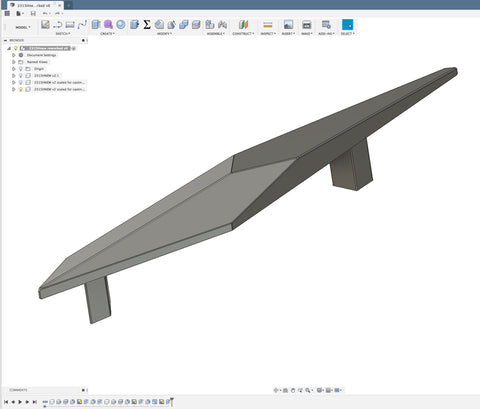

computer model of our elongated shard pull #1

The resources and attention to details paid off when our Peak collection was featured in Interior Design Magazine as a “Best of the Year” finalist for 2016. This led to future partnerships with prominent designers as well as offers of representation from established showrooms.

To create bespoke, handcrafted, functional art is to simultaneously embrace artistic and technical challenges. To conceive and execute designs, from initial concept to finished product, has taken years of experience of learning how to transform failures into successes. Most importantly, this work involves collaborating with the artisans who bring these ideas to life and is also the most rewarding part of the process. I believe that collaboration is the key to evolving, whether it is in what we make or who we become because each relationship holds the potential for something far greater than its origins. Perhaps then, this is only the beginning of the next spark.